The economic costs associated with Covid-19 go beyond those incurred by any other previous crises. A majority of business activities was affected and three economic stimulus packages totaling RM260 billion have been announced by Putrajaya as a fiscal response to ease the burden of the people as well as to support the business community.

However, no measures have yet to be formulated to assist the property sector.

Although the lower interest rate environment created by Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) by cutting the overnight policy rate (OPR) by 50 basis points (bps) to 2% coupled with the 6-month automatic deferment of all loans could help prevent immediate fallout of the property market, these measures are not enough to spur demand.

Given that the property sector’s spill over effect on other sectors can contribute up to 14% of the country’s GDP; measures are needed to stimulate the property market.

Among the measures proposed by industry players are:

1. Extending the Home Ownership Campaign (HOC)

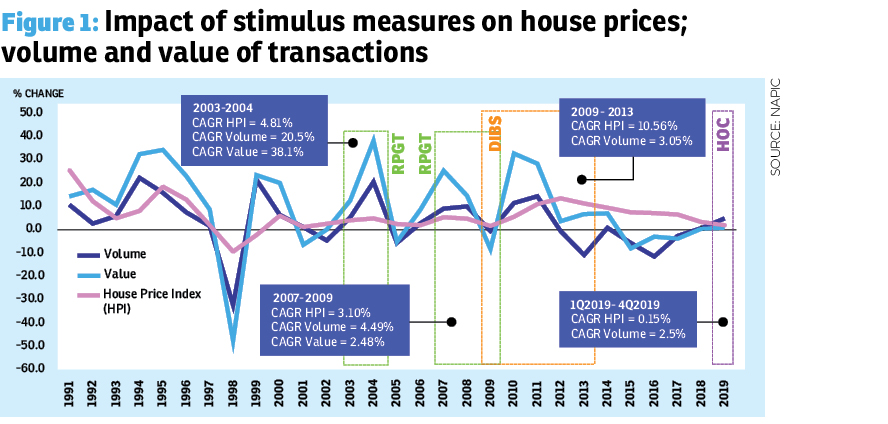

The HOC has been proven effective to stimulate the property market judging from its performance in 2019 where both the value and volume of transactions increased after a four-year contraction. Due to the HOC’s 10% discount off the property selling price and stamp duty exemption on both the instruments of transfer and loan agreements, demand for housing recorded a 5.3% growth and contributed the biggest weightage to overall transaction volume (63.7%) in 2019 (see Figure 1).

However, can the same HOC package boost the current dampened market? In anticipation of reduced incomes and higher unemployment rate, there will be fewer eligible buyers while high-risk borrowers tend to increase.

Hence perhaps additional discounts of 5% to 10% could be more attractive to buyers but this will probably hit the bottomline of many affordable property players, especially of properties priced RM300,000 – RM400,000, what more with the relatively higher development cost following the disrupted supply chain during the pandemic.

The momentum that could be generated by the HOC may also be slower than in 2019 unless developers intensify their digital online presence as people are unlikely to attend property expos in the near term.

The effectiveness of HOC also depends on the duration of its implementation. It is generally perceived that the economy’s recovery will only kick-start in 2021. Should there be another round of HOC this year, a longer campaign period of perhaps 18 months (until the end of 2021) would be more viable to allow potential buyers time to build up their finances.

2. Exemption on Real Property Gains Tax (RPGT)

The exemption on RPGT is often initiated to propel the property market during a recession. RPGT was suspended for a year in 2003/2004, as part of the stimulus package in the aftermath of the September 11 terrorist attack in the US. It was, again, exempted from April 2007 to December 2009, as a measure to shore up the property market which was affected by the sub-prime mortgage crisis. In both cases, the market responded with higher transaction volume and value.

However, by imposing a tax rate of 5% for the disposal of properties after the fifth year since 2019, the RPGT no longer functions to contain speculation. It is now a revenue-generating tax instrument which does not differentiate between long-term investors and speculators.

With the macro prudential and fiscal measures in place since 2010, the speculative herd instinct once prevalent in the market has diminished substantially and the existence of such measures, together with RPGT would worsen the market slowdown.

An RPGT exemption could therefore encourage long-term investments and more people to upgrade. Instead of zero-rizing RPGT across the board, it may be a better idea to revert to the pre-2019 RPGT rate when the disposal of property held for more than five years was zero-rated.

However, one should take note that RPGT exemption in a recession may lead to more sellers as owners and investors who anticipate cash flow problems in the near term will consider selling their assets during the exemption period. This is definitely not helpful to the property market. Instead, to boost buying sentiment, the government can consider allowing those who buy a property within 2020 or 2021 to enjoy a zero-rated RPGT if the property is disposed after seven or 10 years.

3. Lowering foreign property buying threshold

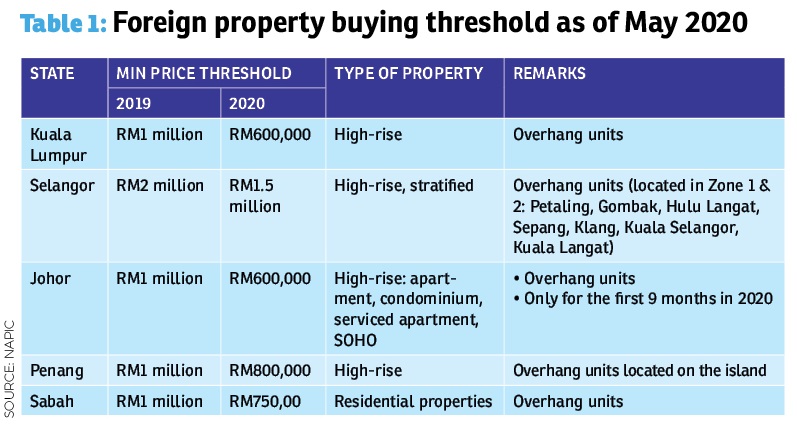

In Budget 2020, it was announced that starting from January to December 2020, the buying threshold for foreign purchasers is reduced from RM1 million to RM600,000 for overhang high-rise units in urban areas.

Such a move may help to spur interest from foreign buyers but the property market is mainly supported by domestic buyers. According to the National Property Information Centre, the number of houses bought by foreigners from January to June 2019 was only 398 units or 0.4% compared with 99,524 units or 99.6% by Malaysians.

Besides, since land and housing are state matters; the federal government can only enforce the minimum price threshold in the Federal Territories. It is still up to the states to revise the buying threshold or not.

Moreover, the move is often controversial as it is perceived as a measure to bail out developers. To ensure the measure attracts only owner-occupiers and not speculators, a better way to implement this is by linking it with the Malaysia My Second Home (MM2H) programme. This is because those who chose to live in Malaysia under the MM2H programme are more likely to behave as residents rather than investors. They are not only bringing higher spending power to the country, but are also contributing to the country’s economy.

4. Reintroducing Developer Interest Bearing Scheme (DIBS)

There is also a suggestion to bring back the DIBS, or to have a modified version of it to boost the market. The interest capitalisation scheme where the developer bears the interest payment of home loans during the construction period was introduced in 2009 as a marketing tool to promote property in the primary market during the global financial crisis. It was prohibited in 2014 to better manage burgeoning real property prices in the country then.

The effectiveness of DIBS in stimulating the property market was undeniable as both the volume and value of transactions during the period of 2009 – 2013 had a CAGR of 3.05% and 17.11%, respectively. However, its impact on property price escalation was also obvious as price growth was recorded as high as 10.56% throughout its four-year implementation compared to a rise of 3.1% in 2000–2009 (pre-DIBS) and 5.9% in 2013–2019 (post-DIBS). Hence, there may be concerns that DIBS would further reduce housing affordability. Considering this, DIBS or any form of it as a stimulus measure is unlikely to be accepted by the government.

5. Loosening lending guidelines

Loan eligibility is still the biggest hurdle to home ownership. Rejection of housing loan applications is higher among low to middle income households who tend to have insufficient disposable income. The situation is expected to worsen after the pandemic, as some may not have a steady income.

There has been a suggestion to review housing loan requirements to assist Malaysians to own homes during the recession. However, with outstanding housing loans going as high as 34% of the total loans in 2019 as compared with 27% in 2007, banks are likely to tighten their lending to reduce exposure to possible defaults from mortgage payments.

While loosening lending requirements across the board may not be viable, the government can, perhaps, consider formulating a more “relaxed” affordable housing scheme for products priced up to RM500,000 as well as to extend the financing tenure to 40 years subject to borrower’s age not exceeding 70 years at the end of the financing tenure. By widening the eligibility criteria, it would not only likely increase the take-up of affordable housing but it can also be seen as an economic empowerment of middle-income households.

The “relaxed” affordable housing scheme can also be in the form of a government credit guarantee for housing loan, in which the government assumes part of the credit risk to act as a shield from risk averseness arising out of lending to medium and high-risk borrowers.

While the measures above had been undertaken in previous crises, we cannot be certain of their effectiveness if they are implemented in the current market as the causes of previous crises were different from the current one.

Dr Foo Chee Hung is MKH Bhd manager of product research & development

Stay safe. Keep updated on the latest news at www.EdgeProp.my

This story first appeared in the EdgeProp.my e-Pub on May 29, 2020. You can access back issues here.

TOP PICKS BY EDGEPROP

One Cochrane Residences

Kampung Pandan, Kuala Lumpur

Union Suites, Bandar Sunway

Bandar Sunway, Selangor

Norton Garden Semi D @ Eco Grandeur

Bandar Puncak Alam, Selangor

Pangsapuri Palma

Bandar Botanic/Bandar Bukit Tinggi, Selangor

TriTower Residence @ Johor Bahru Sentral

Johor Bahru, Johor