Though it has been more than one year since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, it is still difficult to absorb the tremendous impact it has done to the country. Not only is the economy of many Malaysians affected, but far-reaching consequences have also been felt in every aspect of their lives.

After experiencing the deepest ever gross domestic product (GDP) dip in April 2020 (-28.8%), a gradual economic resumption – with growth rate hovering around -3% – was observed throughout the second half of 2020.

Significant improvement over the course of the previous quarters started to be realised in March 2021, when a positive GDP growth of 6% was recorded, followed by a consecutive growth of 40% and 18.9% in both April and May 2021, respectively.

However, due to the reimposition of full lockdown on May 12, 2021 and the surge of new variant cases in the country, economic activities have, once again, been impeded, with GDP growth contracting by -4.4% in June 2021.

As the pandemic continues to rage on, a general “insecure” perception among consumers – linked to business shutdowns, travel restrictions, unemployment and households’ sagging finances – have contributed to a dampened consumer spirit and spending power, thereby leading to a weaker market sentiment in general.

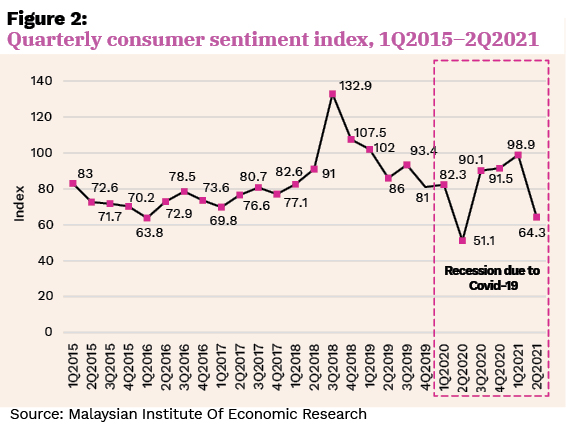

This is reflected in the Consumer Sentiment Index (CSI), where the index dropped to 64.3 in 2Q2021 – being the second lowest since 2Q2020 (51.1) – after scoring above 90 for a consecutive three quarters (Figure 2).

While the latest environment of once-again eased restrictions on Aug 16, 2021 would offer room for economic improvement in the second half of 2021, it will still take time to enhance the market sentiment, as this includes upticks in financial confidence across the board. As a result, the lingering effects of consumer fatigue as well as the associated signs of economic distress would still be prevalent in the remaining quarters of the year.

Only slight growth in Malaysian house price

Being a sector that is highly sensitive to consumer confidence and adverse events, the real estate market is likely to follow the trajectory of CSI, with a softer-than-expected performance as pandemic-related uncertainties persist.

Unlike other developed countries, where house prices are inflating amid the pandemic – mainly driven by the ultra-low interest rates, pent-up housing demand, limited supply, and increased debt-taking ability – Malaysian house prices have only seen a slight growth of less than 2%, despite various relief measures and loan moratoriums offered in tandem with the economic stimulus package.

This, to some extent, is good for the country as it shows that the housing market is not at risk of a bubble; but house prices could still be decoupling from income, thereby weakening people’s housing affordability.

Downgraded housing affordability

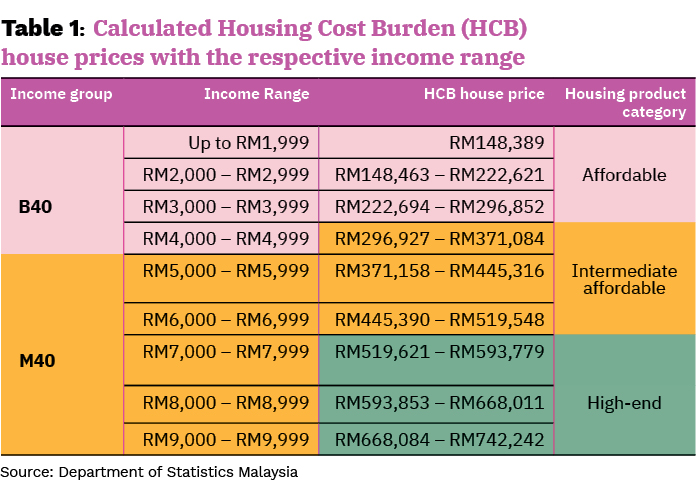

In fact, the pandemic has had a significant impact on people’s salaries and wages; which then further affect the structure of household income groups. For example, by assuming a mortgage rate at 3.5% p.a., with a tenure of 30 years and 10% down payment, coupled with the assumption that the cost of servicing housing loan must not exceed 30% of the net household monthly income; the resulting HCB (Housing Cost Burden) house prices for each income group are as shown in Table 1.

Based on the 2019 household income group categorisation, a B40 household with median monthly household income of RM4,850 is financially eligible for houses priced RM300,000 and below, which is commonly considered as “affordable housing products”.

Some of them may even be eligible for houses priced up to RM370,000, which is within the “intermediate affordable housing products”.

Likewise, an M40 household with median monthly household income range of RM4,859–RM10,959 should be financially eligible for “intermediate affordable housing products” priced RM300,000–RM500,000, and even “high-end housing products” up to RM750,000.

However, as stated in the Household Income Estimates and Incidence of Poverty Report 2020, the current pandemic-induced recession has “downgraded” some M40 households.

Since 20% of the M40 households have shifted down to the B40, their housing affordability level is degraded as well. Consequently, the demand for housing products mainly targeting these M40 households is likely to be impaired too.

This is reflected in the number of overhangs, where in 1Q2021, as high as 53% of the total overhang units are contributed by housing products that aimed for M40 households.

In the case of B40 households, since a large portion of their incomes has been devoted to maintain their daily living expenses, and most of them may not be able to spend up to 30% of their income to serve their housing loans, they may not be even financially eligible for an affordable home.

The significance of people’s income in affecting their housing affordability started to surface when the pandemic struck. Right before the pandemic, one can see that median house price had fallen from RM298,000 in 2016 to RM289,646 in 2019; while the median household income had risen from RM5,228 in 2016 to RM5,873 in 2019. This leads to a decline in price-to-income ratio from 4.8 to 4.1, suggesting that housing affordability in the country has generally been improving in the past few years.

However, a drastic drop in household income to RM5,209 during the pandemic, coupled with a moderate increase in house price to RM295,000 in 2020, has caused an increase in price-to-income ratio to 4.7.

Knowing that wages and salaries are hardly to recover in the short period, while the current pace of house price growth could be maintaining due to the increase in development cost; housing affordability will, therefore, continue to stay challenging in the coming years.

Paradigm shift needed

Clearly, blaming property overpricing as the sole culprit of today’s declining housing affordability is oversimplifying the problem. Whenever there is a drop in housing affordability across the board – where the so called “affordable houses” are no longer affordable to the mass people at present – it is an indication that the problem is not only limited to the mismatch of our housing supply-delivery system.

Instead, it is an economic issue that is deeply related to the country’s weak economic performance. If we are opting for a long-term solution to tackle people’s housing affordability, a paradigm shift is needed. We should move away from the approach that simply aims in building more affordable houses, but to emphasise ways to create more jobs, income growth, as well as helping industries and businesses to survive, to grow, and to transform; which are all key drivers in spurring the country’s economy.

Renting more viable

Under the circumstances that households are generally short of cash, and may even need to make unrealistic compromises in other areas of their lives if they intend to commit themselves to serving any housing loan during the recession; renting could be a better option for them to avoid trapping themselves into the phenomena of “house poor” – a situation where housing expenses have become overwhelming due to an unforeseen change in income.

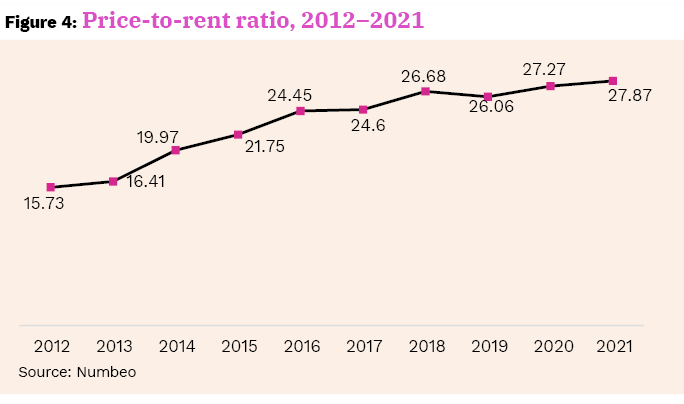

In fact, rents today make a lot more sense than house prices. By studying the price-to-rent ratio for the past decade, one may find that the ratio has been increasing, from 15.73 in 2012 to 27.87 in 2021 (Figure 4); signifying the transition of our property market from a favourable environment for buying a house to a situation where the total cost of homeownership is higher than the total cost of renting.

This is definitely a reflection of the economic hardships caused by the pandemic, but the flatness of rents has been observed for the last few years, even prior to the pandemic, as a result of overbuilding and oversupplying houses. It is just that the current recession is putting additional pressure on the rental market.

Though the number of new housing stock entering the market has dropped in 2020, a glut in the rental market is established, as projects are still gradually adding to completed units.

Inevitably, property investors would have to compete fiercely to attract a limited pool of financially stable tenants, and following the travel restrictions since the virus outbreak, a significantly reduced portion of expatriates, foreign students and local students.

As such, tenants now are in better positions to negotiate prices and this is reflected in a drop in median asking rent prices. However, the other side of the coin is that the country’s property is less attractive as an investment than it was before, given the falling rental yields.

Dr Foo Chee Hung is MKH Bhd manager of product research and development.

This story first appeared in the EdgeProp.my E-weekly on Sept 17, 2021. You can access back issues here.

Get the latest news @ www.EdgeProp.my

Subscribe to our Telegram channel for the latest stories and updates

TOP PICKS BY EDGEPROP

Setia Taipan 1, Setia Alam

Shah Alam, Selangor

Pacific Place @ Ara Damansara

Ara Damansara, Selangor

Bandar Puncak Alam

Bandar Puncak Alam, Selangor

Regent Garden @ Eco Grandeur

Bandar Puncak Alam, Selangor

hero.jpg?GPem8xdIFjEDnmfAHjnS.4wbzvW8BrWw)