CRANES, scaffolding and tractors are a common sight around the Klang Valley. From houses and high-rises to highways and urban transport systems, something is always being built.

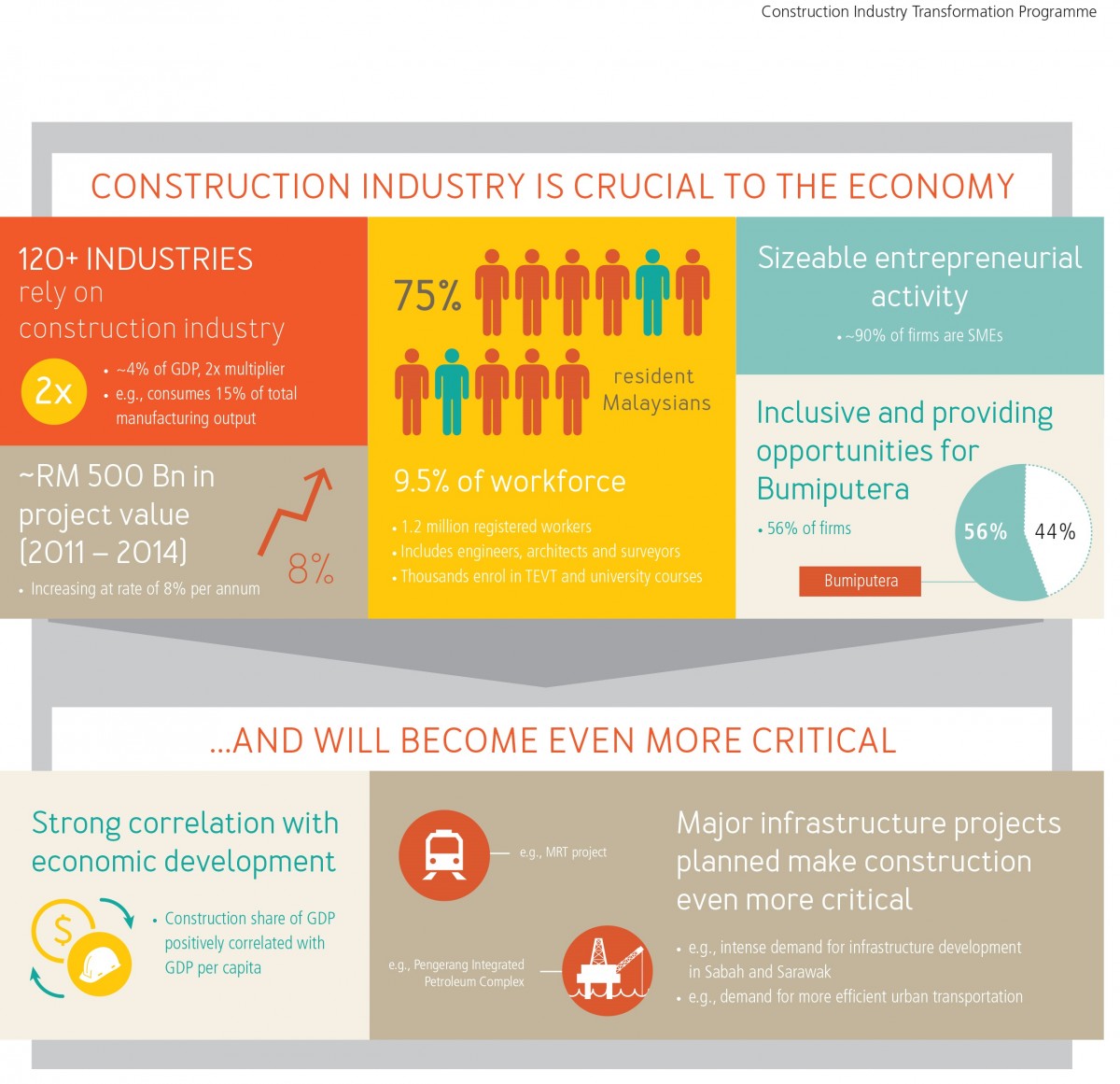

Being a developing nation means construction is always in demand and it plays a crucial role in the economy and growth of the country. The industry also has a multiplier effect, impacting more than 120 other industries.

According to Bank Negara Malaysia, the construction industry contributed about 4% to the country’s gross domestic product as at 2014. It is expected to increase to 5.5% up to 2020. The 11th Malaysia Plan notes that the government expects the industry to expand by 10.3% per annum over the next five years.

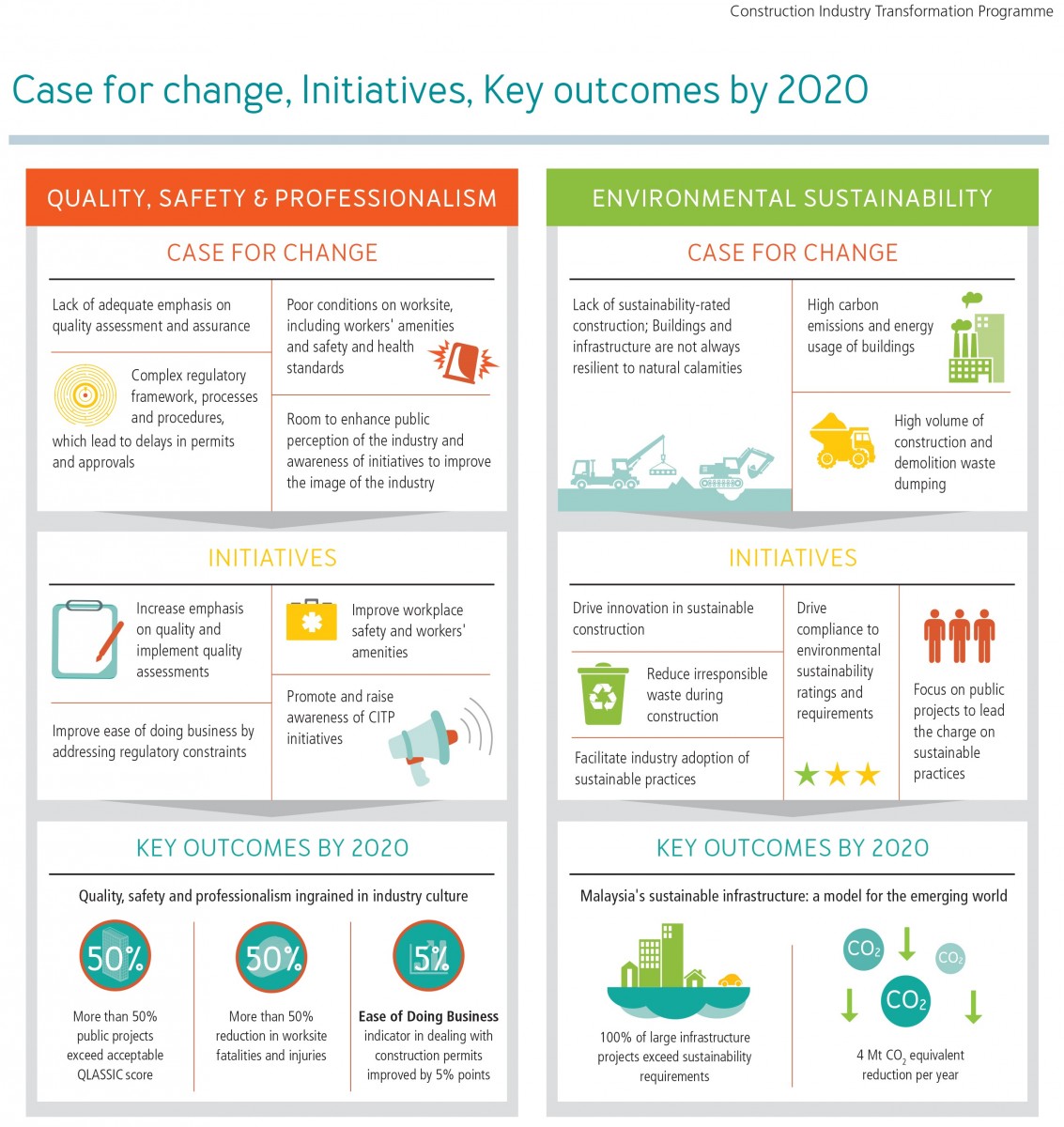

Despite the rapid growth of the industry, issues — some long-standing — remain. To tackle them and elevate the industry, the Ministry of Works, through the Construction Industry Development Board (CIDB), developed the Construction Industry Transformation Programme last year. CITP has four strategic thrusts — quality, safety and professionalism; environmental sustainability; productivity; and internationalisation.

City & Country speaks to CIDB chairman Tan Sri Ahmad Tajuddin Ali about the current state of the construction industry, the need for CITP and ways to address the key issue of safety and health in the industry.

City & Country: Why is there a need for CITP?

Tan Sri Ahmad Tajuddin Ali: The construction industry, being a key enabler of economic growth, is very important. We want to be able to export our services, we need overseas jobs, but at the moment, we are losing jobs to foreign contractors, even the local ones.

There are things that are not happening the way we want in respect of safety, the environment, productivity and sustainability. These are the key areas we need to address if we want to enhance and upgrade the sector.

We had strategies and action plans in place before CITP and we have gone some way. The industry has changed and there is still a lot to be done. CITP is a new approach that encompasses the current challenges facing the industry.

One of the pressing issues to be addressed and one that will positively impact the strategic thrusts is safety and health.

What is the current safety and health status of the industry?

At present, we are nowhere near happy and the situation needs critical intervention. At 10.94 fatalities per 100,000 workers, it is among the worst-performing industries, alongside services, agriculture and manufacturing. The average fatality rate across all industries is 6.93 per 100,000 workers.

In 2014, there were 89 fatalities in the construction industry, and the number jumped to 140 last year. From January to March this year, the industry registered 17 fatalities out of 42 across all industries.

Of course, accidents do happen, but there is an urgent need to look at where we are and how we can move forward. Apart from injuries and the tragic loss of lives, accidents at worksites cost money. They result in stop-work orders and loss of working days. And we don’t want people dying unnecessarily.

Even though the number of fatalities is low when compared with vehicular deaths — 14 to 16 a day — it should be much lower or none at all with proper management.

Is there a set target to reduce the fatality rate?

The CITP target under the quality, safety and professionalism thrust is to halve the number of fatalities by 2020. To achieve this, we must work hand in hand with all stakeholders to instil a safety culture in workers. Policymakers must commit themselves to change their policies in favour of safety and health.

CIDB and the Department of Occupational Safety and Health (DOSH) have signed a collaborative pledge to leverage each other’s resources, expertise and legislative power to work towards achieving the target. This is definitely a step in the right direction. There are many more stakeholders which we must engage in order to move the industry towards that direction.

The effort has to be continuous because bosses and workers change all the time. Training programmes need to be carried out. Even drills at sites are important. Some people say all these will take time, but that’s an investment you need to make in order to ensure accidents don’t happen.

Japanese companies hold short talks in the morning before starting work so that everyone knows his or her job. This is a continuous effort.

To instil a new culture in people often means changing mindsets, which is always difficult. How can CIDB do this in its capacity as the industry institution?

That is one of the reasons why the collaboration with DOSH is important. We are upstream, we educate and introduce systems that can lead to better safety at the workplace. Our hands are tied when it comes to enforcement because it is not our role. But if we do our job right in terms of educating the workers and getting the companies and contractors to behave appropriately, there will be fewer incidents.

Our power is only within the context of our own act, which is mostly administrative. At the other end is the DOSH, which has the power to investigate and prosecute. Together, our agencies will work towards a common goal.

Policymakers need to drive change in the construction industry. In the private sector, they are the board of directors and the top management of companies. There must be a commitment from the C-level or top executives that cost, schedule and quality do not take priority over safety. And this commitment must cascade down the line. This is why we want to drum into them that safety starts from the top.

It is good business sense, yet it is often not taken seriously and not emphasised enough by management. Accidents can lead to loss of lives, time, reputation and money.

Management needs to promote a safety culture through systems, incentives and whatever measures necessary. If the message is strong and clear from the top, the staff will adopt the right procedures and structure to live the company’s philosophy. To me, that is where it starts and what we are trying to build into our action plans — education at the highest level.

For developers, they must draw up policies and terms that their contractors must abide by. The same goes for big contractors; they can set policies and terms for their subcontractors.

Owning and leading a large organisation comes not only with lucrative pay and benefits but also huge responsibilities. Most corporate leaders understand their responsibility in terms of the bottom line. But what about ensuring the safety of workers and the public? This should not take second place.

What are the initiatives within CITP to reduce the number of accidents? How do you get the private sector to do this?

Among the items proposed at the CITP initiative working group level is the inclusion of safety and health elements in contracts for both government and private projects. The target is to make this mandatory for government projects by 2020 ... this is still in the proposal stage. For the private sector, putting the safety and health elements in contracts is a best practice that needs to be adopted.

CIDB has developed the Safety and Health Assessment System in Construction as a voluntary best practice assessment to identify any loophole or flaw in safety at any construction site. The report can be used by the respective firms to enhance their safety adherence and close the gaps where needed. It needs to be made known that there is definitely a cost in implementing a safety programme. But the value of a life is much greater compared to the money spent to ensure safety. But even if we talk about ringgit and sen, the cost of investing in a solid safety programme will certainly pay off handsomely through a substantial reduction in costs attributed to loss of man-hours or down time from closure of sites because of stop-work orders.

The best we can do to encourage this is through seminars, conferences, demonstration of good practices and so on. All workers are required to go through basic safety training, but the training with the biggest impact would be the one with the top management.

How confident are you of achieving the target?

I think it is a tall order and the industry needs to make a tremendous shift in attitude and behaviour for it to happen. Having said that, I believe it is an achievable target. The industry has been tolerating too many injuries and fatalities ... this shouldn’t be the case.

We already have examples of other industries that were previously considered high risk but have committed to put safety as a top priority and have been successful in maintaining clean safety records for years. The mining industry is one of them.

In Canada, the mining industry has moved from what was once regarded as highly physical and often dangerous business to a sophisticated sector that makes use of automation. As a result, safety records have improved significantly and the industry today is one of the safest in Canada. Even if we look at the mining industry in Malaysia, including the oil and gas sector, there were no deaths recorded from January to March this year, compared with 17 in the construction industry. Even compared with the other industries, mining has the best safety record.

In the earlier years of green ratings in Malaysia, the government has given incentives to companies for achieving such ratings, which has worked to a certain degree. Has CIDB considered doing the same to encourage companies to achieve a zero-accident workplace?

I like that you mentioned incentives. The other day, during the launch of MyCREST (Malaysian Carbon Reduction and Environmental Sustainability Tool), the first question asked was, what are the incentives? People should not be doing the right thing because of incentives.

The same question was raised during a campaign to encourage the use of seat belts by the Ministry of Transport years ago. I was thinking, wasn’t saving your own life incentive enough? There shouldn’t even be a need to make it compulsory for people to fasten their seat belts because it saves lives.

So, I’m not for incentives. I don’t understand why incentives are needed when you are asked to be do something that is good for you. Perhaps companies themselves can reward the relevant departments or project teams for achieving a certain number of hours of zero lost time incidents. That is the correct way of doing this.

Don’t do things for the wrong reasons. Do it because it is good for you and the company. Companies should compete to have the best track record.

One of the key areas that can have a significant impact on not only health and safety but also productivity is the adoption of mechanisation, modern practices and the Industrial Building System. IBS, in particular, has been on the government’s agenda for years but till today, the uptake has been very slow. What is being done to change this?

The government has been pushing for IBS as the method of construction as it solves many issues, including safety, quality and sustainability. It even reduces the need for low-skilled labour. By having building components manufactured in factories and assembled on-site, most of the work will be done off-site. The components will be installed using machinery and this will significantly reduce any safety risk, as opposed to having numerous non-skilled personnel working at the site.

However, it will need some investment in technology and the development of specific skills. Unfortunately, it is a chicken-and-egg situation — it is easier to do things the way we are used to and after all, the company is still making money. There will be risks when you go into the unknown. Some elements of IBS and modularisation have taken place but they are still not the prevalent methods of construction.

The push for the adoption of IBS is ongoing and it is even a requirement for government contracts ... contractors must apply a certain percentage of IBS in the projects. It is happening, but not happening fast enough.

I’m sure one day when our labour cost has risen to a high level, companies will start looking at IBS. Until then, no one is producing IBS components because there is no market for them, and there is no market because no one is producing IBS components. One is feeding into the other.

This article first appeared in City & Country, a pullout of The Edge Malaysia Weekly, on Aug 29, 2016. Subscribe here for your personal copy.

TOP PICKS BY EDGEPROP

Biji Living (Seventeen Residences)

Petaling Jaya, Selangor

Ryan & Miho @ Section 13

Petaling Jaya, Selangor

Biji Living (Seventeen Residences)

Petaling Jaya, Selangor

Pandan Villa Condominium

Pandan Indah, Selangor

Bandar Tun Hussein Onn

Batu 9th Cheras, Selangor

Bandar Damai Perdana

Bandar Damai Perdana, Selangor