After just about two months in office, new Housing and Local Government Minister Datuk Seri Kong Cho Ha feels there is a need for change — not in the ministry but in the people’s perception of it.

People tend to blame the ministry for all their housing-related woes, so making them understand the role of the ministry better is one of his key challenges, says Kong.

“They must understand that we are here to help them, not to be blamed for their problems. There are various forms of redress under the law or through the Housing Tribunal. At the same time, we would like housing developers to be more responsible, have good governance and ensure that buyers get what they pay for,” he says.

The ministry is committed to ensuring the growth and success of the housing industry and to protect the interests of homebuyers, Kong asserts, but it finds it a challenge to resolve some of the concerns raised by developers and homebuyers as these are outside the purview of the ministry.

“People must know that there are certain areas which are under the state government’s jurisdiction and not handled by the federal government,” says Kong, who is an MCA vice-president and former deputy finance minister.

For example, in the ministry’s resolve to provide sufficient public housing for the lower income group, it is faced with the challenge of building homes in the right location to avoid a mismatch between demand and supply. However, says Kong, it is the state government that identifies the sites for public housing schemes, not the federal government.

“The state government registers the names of those people who wish to own these houses, identifies the land for the project and then works with federal government agencies to implement the schemes. So, very often, the federal government does not have much say in choosing the location and it does not play any role in identifying the buyers at all,” he explains.

Therefore, “the state government has to be wise enough not just to meet the numbers but also be aware of the consequences of its decisions. In this case, in choosing the location for the houses, it must ensure these are built in places where the people want to live”.

Kong adds that buyers are only informed about the location of the houses after these are completed. “People from the lower income group usually do not have their own means of transport, so they expect to live near where they work. If they find that the house is very far from their workplace, they will not take up the unit.”

However, there are some aspects of the public housing schemes that the federal government can decide. In fact, says Kong, the government is mulling changes in the design of low-cost houses to improve living conditions.

“We may have larger floor areas. Right now, the units are around 600 sq ft per unit, which is not very conducive to a growing family.

“The government also wants the country to become a higher income nation, so the design of our public housing schemes should reflect its aspirations. These are some of the things we can look into.”

As for the bumiputera housing quota, Kong says the federal government cannot respond to calls by developers to review the release mechanism for unsold bumiputera units to standardise it and make it more transparent.

“That is another issue that is left to the discretion of the state governments. If the mechanism retards the growth of the state, then the state government should rethink it,” he says.

“Different states have different guidelines and their own way of implementation and release, thus we cannot help much,” he adds.

When asked if the ministry is willing to bring everyone to the table to discuss the issue, Kong replies: “It depends on whether they are willing to listen.”

As for the current property market slowdown, Kong says he is confident the local housing industry is mature and resilient enough to cope with it.

“In any economic situation, good or bad, there will be people who want to buy houses in good locations. So the prices in these areas will go up even during bad times. During the good times, there will still be houses that people do not want to buy, maybe because of the location.”

This means developers need to be well informed about what the market wants. “I think our developers, especially the more established ones, know what they are doing and know what the market wants. Whether they develop or not is based on their market research and studies. If they do enough research, they will be fine even in a downturn,” says Kong.

Abandoned housing projects

The number of abandoned housing projects has dropped over the years and according to the minister, the ministry has not seen a spike in stalled projects despite the current market downturn.

Kong says in the 1990s, the number of abandoned housing projects accounted for 1.8% of the total number of houses built. Today, this figure has fallen to 0.9%. “Our records show that the number of buyers affected is about 30,000-odd compared with the millions of houses built. If you compare any industry average rate of failure, I think the figure is pretty good.”

As for half-completed projects, the government will seek “white knights” to take over these. In other cases, the ministry will act as mediator between the buyers and the developers to come to a solution.

Still, Kong admits that there are some complicated cases that are almost impossible to untangle, such as those that involve litigation, the court or land matters.

A Special Task Force for the Rehabilitation of Stalled Housing Projects, headed by the Chief Secretary to the Government and comprising senior officers from the relevant government agencies and private sector representatives, has been set up to look into abandoned housing projects.

Up to April 30, 146 housing projects had been abandoned by private developers. The states with the most stalled housing projects were Selangor with 40, Johor (33) and Negeri Sembilan (20). A total of 142 companies and 479 directors have been blacklisted as of March 13 after their housing projects stalled. The names of the companies and directors are posted on the ministry’s website www.kpt.gov.my.

Although there is a blacklist, no one can deny the possibility of a rogue developer operating his business using the names of nominees. “People are creative. We just have to work within the system,” says Kong.

He says the government has to be wise in dealing with the issue. “Bailing out developers who are in financial problems would not be a very wise thing to do. If we keep pumping in money to save them, I think there will be more abandoned projects as the system can be abused. Is it fair to taxpayers since we will be using their money to save these projects?”

On his priorities as the housing minister, Kong says he wants to continue with the measures and initiatives implemented by his predecessors and to improve them when the need arises. He is confident that the decades of development the Malaysian housing industry has gone through will translate into greater maturity and growth in the sector.

This article appeared in City & Country, the property pullout of The Edge Malaysia, Issue 758, June 8 – 14, 2009.

TOP PICKS BY EDGEPROP

Bandar Bukit Tinggi

Bandar Botanic/Bandar Bukit Tinggi, Selangor

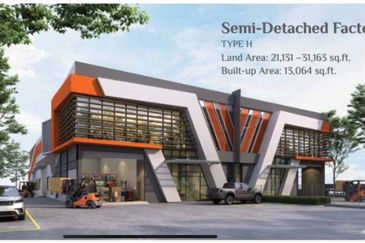

Taman Perindustrian Desa Cemerlang

Ulu Tiram, Johor

Taman Perindustrian Desa Cemerlang

Ulu Tiram, Johor

Taman Perindustrian Desa Cemerlang

Ulu Tiram, Johor

Taman Perindustrian Desa Cemerlang

Ulu Tiram, Johor

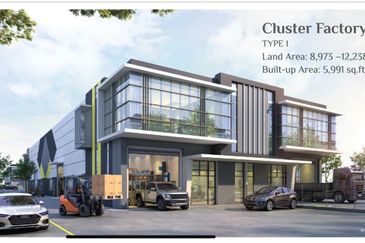

Taman Perindustrian Sri Plentong

Masai, Johor

Apartment Tanjung Puteri Resort

Pasir Gudang, Johor

hero.jpg?GPem8xdIFjEDnmfAHjnS.4wbzvW8BrWw)