Reduce parking to reduce traffic congestion

- A change in parking policy should be integrated into future residential planning to alleviate our traffic woes.

KUALA LUMPUR (April 16): Traffic congestion is a mired and unsettled problem in nearly every modern society. With the increasing urban sprawl, population growth, longer travel distances and demand for higher standards of travel, can a city can move away from the private car-dominant mode of transport?

Countries are looking for alternatives to address this pressing issue; and designs that favour walking, cycling and public transport are perceived as effective strategies.

Transit-oriented developments?

Among them, transit-oriented-developments (TOD), which integrates land use with transport by forming compact, mixed-use, and pedestrian-friendly neighbourhoods around major transport hubs, bring people and activities closer together in functional, walking- and cycling-oriented places. Like many other cities around the world – Stockholm, Copenhagen, Hong Kong, Tokyo, and Singapore – Malaysia has been increasingly embracing the TOD concept, particularly in the highly urbanised Klang Valley.

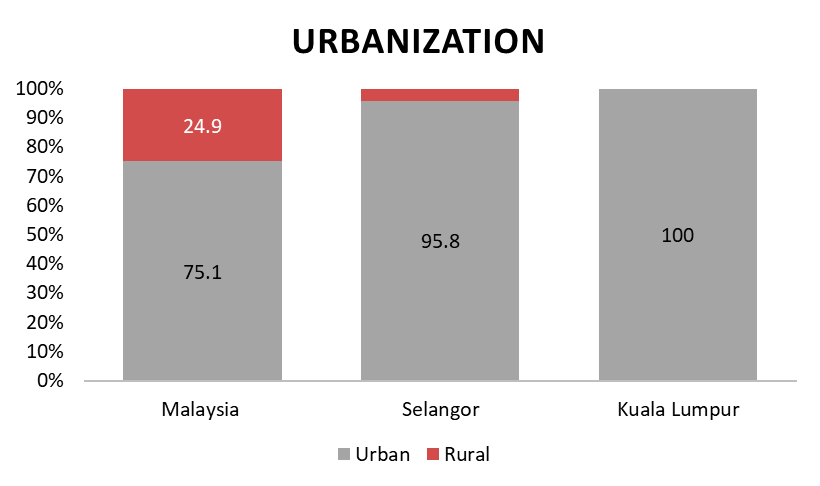

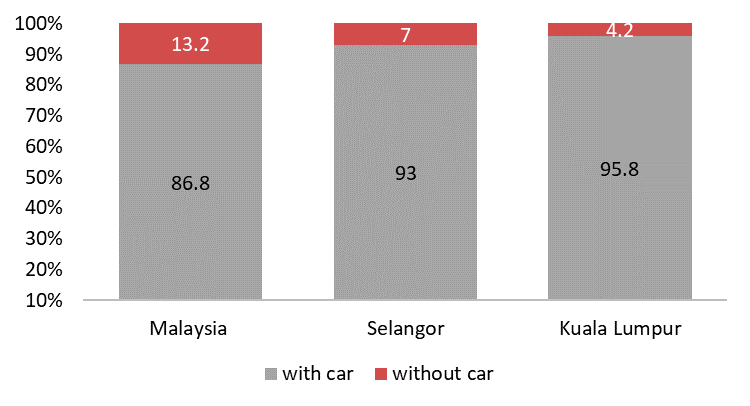

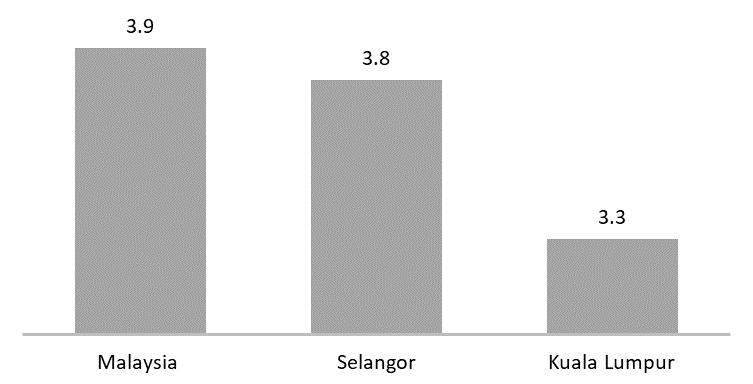

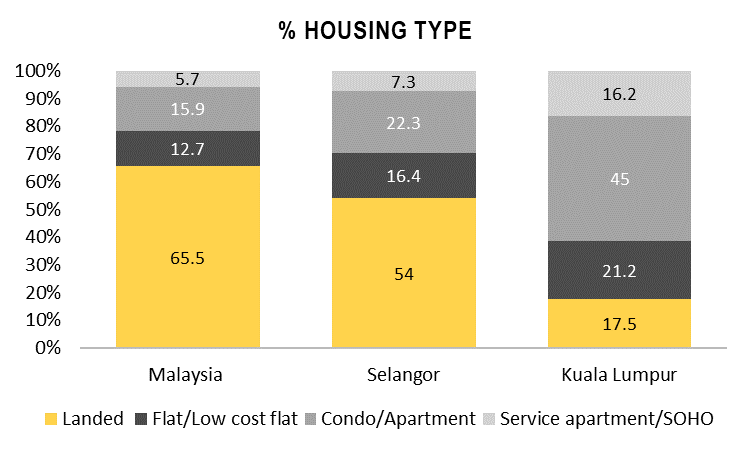

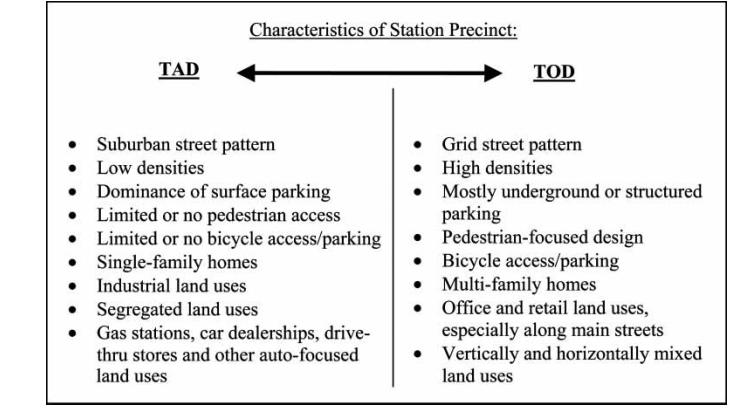

High car ownership and urbanisation rate, declining average household size, and a changing landscape towards a vertical city are key factors that support the TOD concept in the Klang Valley (Figure 1). However, with limited transit catchment areas coupled with the lack of last-mile option to and from the transit station, many developments that have been labelled as TOD are more like “transit-adjacent developments” (TAD) instead.

In contrast to TOD, TAD are physically near transit but fails to capitalise upon this proximity because of its lack of functional connectivity to the transit in terms of land-use composition, means of station access, and site design. In fact, there is a lack of fully integrated and functional TOD like KL Sentral. Most transit stations fall between the spectrum of TAD and TOD (Figure 2).

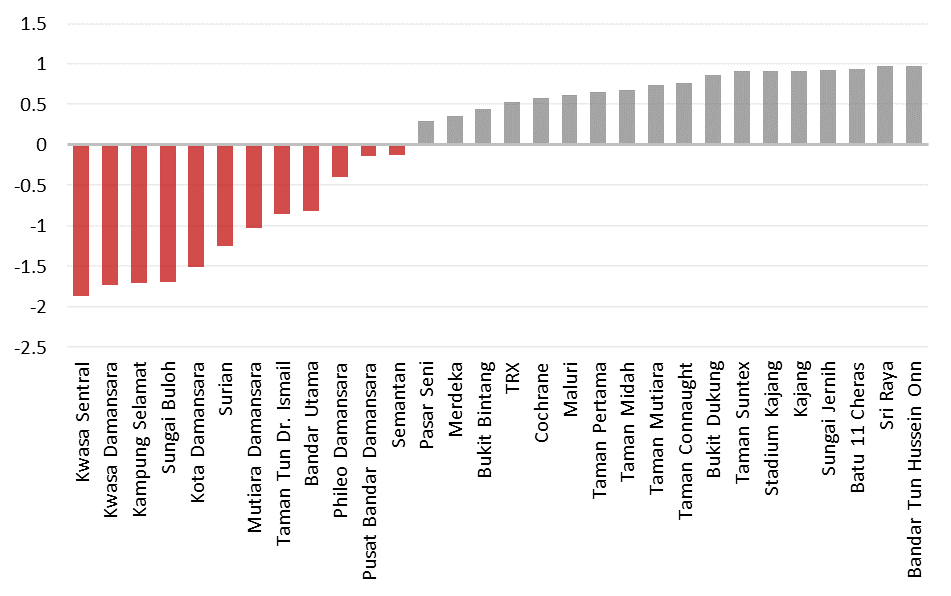

This is evidenced by the Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) Sungai Buloh-Kajang Line – straddling the Klang Valley region from north to south – where not all stations along this line fulfil the aspiration of a genuine TOD (Figure 3). Insufficient placemaking has failed to turn these transit stations into the focus point of the surrounding neighbourhoods, or bring in the required densities and mix. This is particularly true for stations at the urban fringe, where they still lack the transit-focused planning, quality and range of amenities, diversity of site use and housing and walkability needed for vibrant and sustainable communities to emerge. Thus, it makes public transport less efficient in terms of coverage, reliability, speed, convenience and comfort compared to driving.

% housing type (2022)

Rail transport?

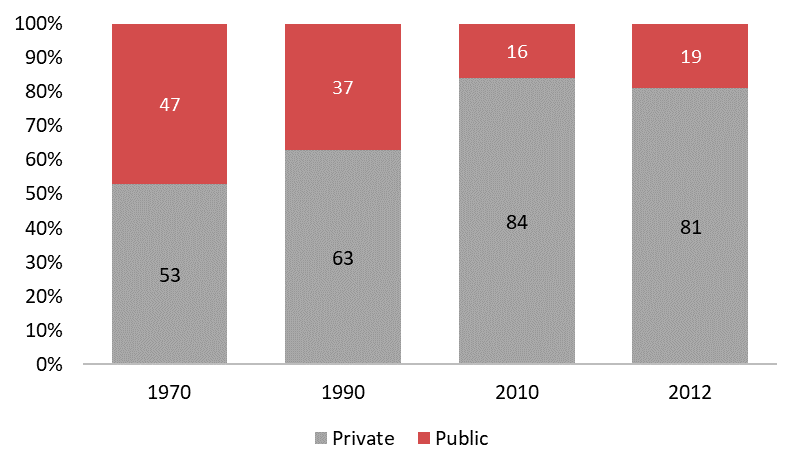

Though the rail transport in Malaysia has long been established, it is still not showing encouraging progress in terms of ridership. For instance, the mode share of public transport has been deteriorating since 1970, as transport development in the Klang Valley has mainly focused on the road network (Figure 4).

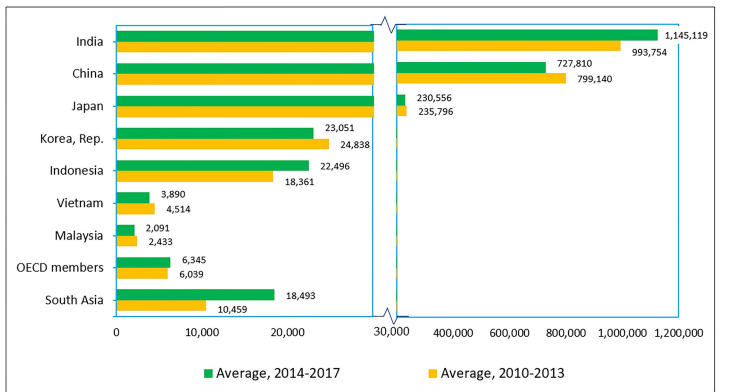

As a comparison, the number of railway passengers per unit length in Malaysia is far behind compared to India, China, Japan and South Korea. Even in Southeast Asia, Malaysia is still behind Indonesia and Vietnam (Figure 5).

We should realise that our city’s traffic congestion is the result of our urban development that has made a driving-based lifestyle the norm of our society. Rail transits do provide an alternative mode of transport, but fail to induce a change in the travel preference from private to public.

Therefore, TOD alone cannot contribute effectively to the reduction in car ownership and usage without deliberate policies to suppress travel demand. As long as there is a high car ownership rate with a large pool drivers wanting to travel at the same time of the day – coupled with the affordability of cars and fuel – there will be an ever-increasing number of motorists and lengths of motorised trips, leading to recurring traffic congestion.

Home parking encouraging car ownership

To reduce traffic congestion, policy makers and land-use planners should consider ways to suppress the use of private vehicles. Besides introducing charges within high-traffic zones (as practised in Singapore, London, Stockholm, Sweden, and Milan) or car licence plate auctions for the right to buy a car (as practised in Shanghai and Beijing); revising the current parking policy is a critical but overlooked instrument that we should try, given that Malaysia is one of the countries with the most vehicles per person.

There is growing evidence suggesting that home parking availability can induce more car ownership. No doubt private cars have advantages in facilitating personal mobility while giving a sense of security and status. Especially in developing countries, households that own reserved parking have higher likelihoods of owning cars. They then tend to make more car trips and drive further if there is good access to off-street parking. They also tend to choose the car even to destinations that are well served by public transport if parking is generous.

Minimum parking requirements

The implication here is, parking policy must be an integral part of a systematic approach to transport planning in future residential developments. It should be carefully introduced according to the dynamic logical relationship between parking supply and private car trips. A tool that is increasingly seen as an effective means of regulating car ownership and usage is the minimum parking requirements (MPR).

Globally, MPR were introduced into planning schemes in the 1950s to address rapidly increasing vehicle use and pressure on public parking resources. At their core, MPR require each development to provide a minimum quantity of parking based on an estimated peak demand, for example, per bedroom at a hotel, floor area of a retail store, or classroom in a school.

Likewise, residential parking is traditionally subject to minimum norms. In the case of Selangor, the highest requirement is set at 1:2.2 for serviced apartments – where two car parks are required for each dwelling unit, plus another 20% of visitor car parks based on total dwelling units, regardless the size, be they 550 sq ft or 1,000 sq ft); or whether the development is transit oriented or not (Table 1).

Though the rationale is to meet the increasing demand for car park due to high household car ownership, as well as to resolve demand for on-street parking that new developments bring; the requirements are rarely based on empirical evidence. Instead, they are pragmatic rules and quite often a result of historic developments or replications of practice in neighbouring areas.

More importantly, MPR not only tend to encourage higher car ownership and more congestion; but also impose unexpected impacts on the overall urban built environment.

Table 1: Minimum requirements for residential parking in Selangor

|

Type of Development |

Minimum Parking Requirement (MPR) |

|

|

High-rise residence |

Low-cost apartment (700 sq ft) |

1:1.2 |

|

Low-medium cost apartment (750 sq ft) |

1:1.2 |

|

|

Medium cost apartment (850 sq ft) |

1:2.2 |

|

|

Free-market apartment (1,000 sq ft) |

1:2.2 |

|

|

Serviced apartment |

500 – 1,000 sq ft |

1:2.2 |

|

Every increment of 500 sq ft |

Add one more car park |

|

|

Rumah Selangorku |

Solo (450 sq ft) |

1:1.2 |

|

Duo (600 sq ft) |

1:1.2 |

|

|

Trio (750 sq ft) |

1:1.2 |

|

|

Quad (900 sq ft) |

1:2.1 |

|

|

Landed residence |

Car porch is available for every unit |

|

(Source: Manual Garis Panduan & Piawaian Perancangan Negeri Selangor; Pekeliling Lembaga Perumahan dan Hartanah Selangor (LPHS))

MPR take too much land

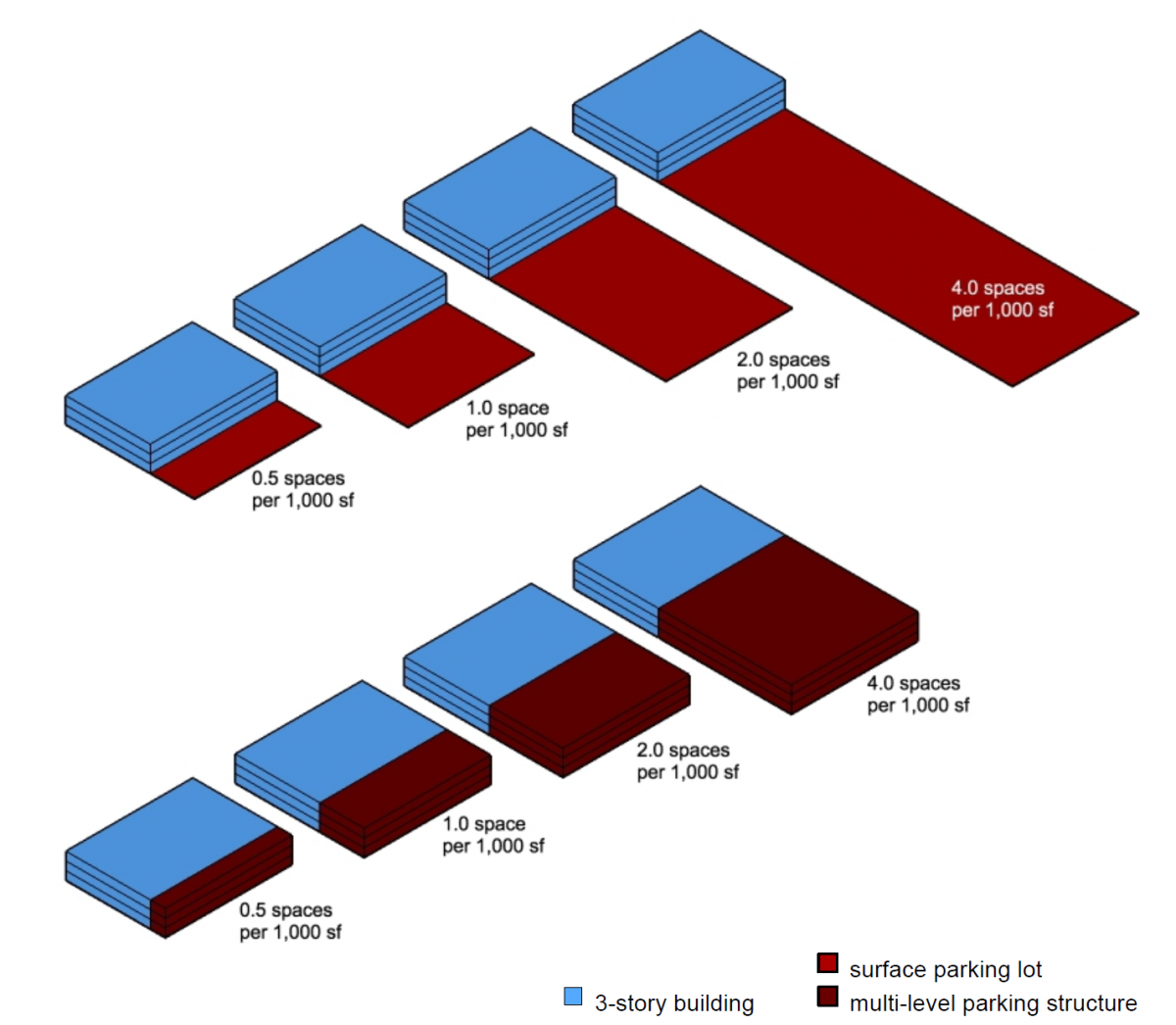

One of the biggest concerns with MPR is that it takes up surprisingly large proportions of developed land. Space devoted to on-street parking means less space for traffic lanes, footpaths, street trees, commercial space or public open space; while space devoted to off-street parking limits its potential for other higher-value usage. For example, a requirement of two spaces per 1,000 sq ft (or one space for every 500 sq ft) – a common parking requirement for commercial developments in Malaysia – implies that space devoted to parking is almost equivalent to 70% of the useable building space (Figure 6).

As urban areas become more crowded, MPR can be problematic, especially in prime areas, as more spaces are needed to accommodate them. To ensure the project feasibility in these areas, large podium car parks are normally built below the towers. Eventually, new buildings become taller and parking structures with larger footprints become the dominant features of the built environments.

Aesthetically, building design and architecture are compromised, because unattractive large parking spaces overwhelm the physical landscape of the city, thereby undermining the quality of the street.

While there are ways of meeting parking requirements without impacting the built environment, such as through underground facilities; this method is costly and only feasible for large-scale projects.

Valuable space left unutilised

The situation becomes worse during the slowdown as overhang units lead to a large number of unutilised parking spaces. This is because the numbers suggested by MPR are based on predictive variable and demand ratio estimation processes that are in line with the conventional low-density parking policies, aiming to provide abundant parking supply. A steadfast adherence to this leads to the oversupply of parking lots, which also reduces housing affordability.

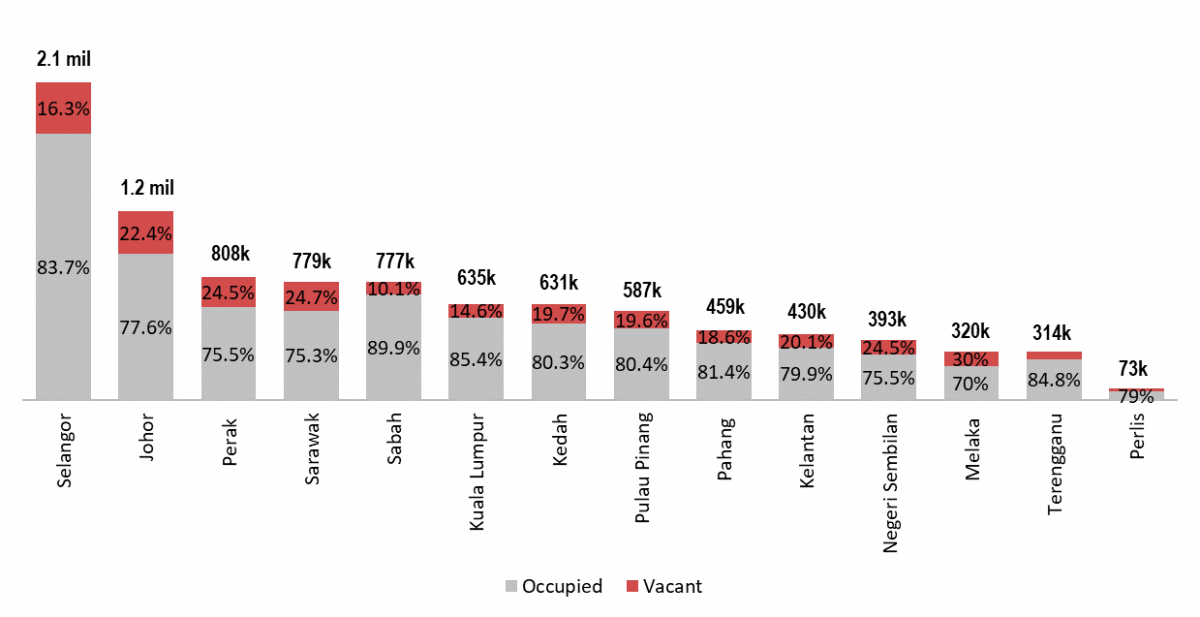

As shown by the Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM), living quarters in Malaysia amounted to 9.6 million in 2020, out of which, 1.9 million are vacant units – 22% were in Selangor, 13% in Johor, 8.5% in Perak, 8.2% in Sarawak, 8.1% in Sabah, etc. (Figure 7) – reflecting a steep increase from 700,000 in 2010. With a parking supply that is “locked in”, MPR has contributed to the problem of unutilised land, as parking lots are often the single largest land use (typically 30%-50%) in such areas, thereby undermining a more efficient and sustainable urban development.

Unnecessary increase of housing cost

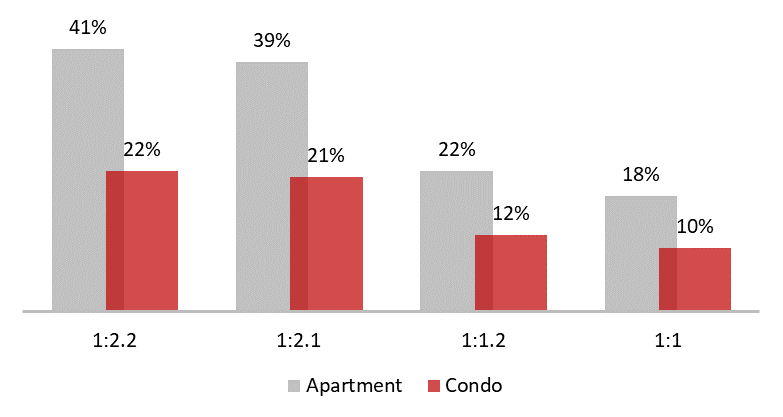

What is more concerning is the cost. A parking space is worth about 18% of an average standard apartment unit if one car park is required for each dwelling unit; and 41% if the parking requirement is 1:2.2 (Figure 8). The cost impact imposed on the former is obviously greater as this type of housing – targeted for low- and medium-income groups – often involves higher land price but with capped selling prices.

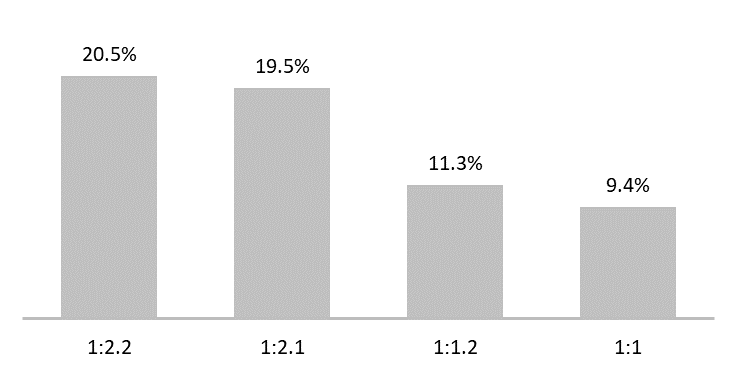

Increased parking requirements lead to increased housing development costs, and thus, reducing housing affordability. As shown in Figure 9, one car park adds about 9.4% to the unit cost; 11.3% more for an additional 20% visitor parking; and 20.5% more for doubling the parking space.

In areas where land costs are high, the best way to increase affordability is to increase density and reduce parking facility requirements. If housing can be built and sold without parking, or with reduced parking requirement, the house price would be lower.

Shifting towards flexible parking standards

At the same time, to reduce car use and control urban traffic congestion, the government should implement flexible parking standards (FPS) instead of MPR.

New parking management strategies have been recently used by several cities in Europe to manage congestion and create a more attractive built environment. For residential buildings, FPS allow for reductions in the number of parking places, provided other solutions, such as car-sharing, are available.

This new paradigm places more emphasis on “minimal (not minimum) parking standard” and management solutions. Here, “minimal” means “the smallest possible number”. It recognises the need to provide adequate parking, but values strategies which result in more efficient use of resources..

Rather than providing parking requirements to satisfy the maximum potential demand that may occur during the lifetime of a facility, an alternative parking management allows for contingency-based planning. Various solutions are identified, which can be deployed if needed. For example, instead of insisting on MPR of 1:2.2, FPS may provide 1:1.3 or 1:1.4 (one car park for each dwelling unit plus 30% or 40% of visitor parking lots along with various parking management strategies).

By reducing the basic requirement to one parking, housing costs are reduced; leading to more affordable housing. By unbundling parking from housing, households only pay for parking facilities based on the number of spaces they actually use; while those who require more parking spaces can opt for season parking from unutilised visitor parking.

The FPS and parking management should be within a paradigm of sustainable mobility and multimodal accessibility, where they form part of urban planning and design policy for sustainable development and change. Investments in infrastructures for walking, cycling and public transportation should allow for lowering of parking standards and redesigning cities. In a virtuous cycle, less parking would lead to more walking, cycling and transit use, and contribute to a modal shift towards environmentally-friendly mobilities and decrease in carbon emissions and oil consumption.

Dr Foo Chee Hung is MKH Bhd manager of product research and development.

Never miss out

Sign up to get breaking news, unique insights, event invites and more from EdgeProp.

Latest publications

Malaysia's Most

Loved Property App

The only property app you need. More than 200,000 sale/rent listings and daily property news.