Property Chat: Do we lack affordable houses in Selangor?

It is heartening to see that the government, through the 12th Malaysia Plan (12MP), has outlined a more holistic approach to affordable housing as an attempt to reform the housing market in the post-Covid-19 era.

Efforts are devoted not only to the demand side through the provision of financing facilities for first- time homebuyers and the rent-to-own (RTO) housing programme for poor and low-income households; but also to include ways to reduce cost of doing business on the supply side, such as standardising charges and fees imposed by local authorities and utility providers for the construction of affordable housing, reviewing the existing industrialised building system (IBS) incentives, capitalising on government-owned and waqf land for the development of affordable housing for selected target groups, etc.

On top of that, a data centre on housing – by integrating relevant data from the federal and state governments as well as private developers – will be established to strengthen the institutional capability in monitoring the supply of affordable housing. Also, public affordable housing programmes such as Perbadanan PR1MA Malaysia, Syarikat Perumahan Negara Bhd (SPNB), and Program Perumahan Penjawat Awam Malaysia (PPAM) will be centralised under the Ministry of Housing and Local Government (KPKT) for better governance and coordination.

Apparently, the national housing policies are directed towards the building of adequate, quality, and liveable affordable houses, with the aim to increase homeownership among low- and middle-income groups, which has likely been impaired by the pandemic-induced economic recession. This is evidenced through the renewed commitment to build a total of 500,000 affordable houses through initiatives such as Rumah Mesra Rakyat, Residensi Wilayah and Program Perumahan Rakyat under the 12MP.

This will definitely set the tune for the budget plannings of both the federal and state, in terms of strategising ways to increase the supply of affordable houses, so as to contribute towards an improved national housing affordability level. A typical example of this is the latest announcement made by the Selangor government on the new affordable housing scheme – Rumah Idaman.

Having said that, the initiative of “building 500,000 affordable houses” tends to give the impression of meeting the key performance indicators (KPI) or chasing the figures – a response to the social pressure in providing acceptable housing standards at an affordable price for low-income groups – rather than an appeal to the economic supply and demand principle.

Experiences from the existing price-controlled social housing schemes like PR1MA and Rumah Selangorku (RSKU) have shown that building more affordable houses is neither the answer to the problem of housing affordability nor overhang in the country.

Instead, it gives rise to the problem of cross-subsidisation and poses threats to the balance of the housing industry ecosystem, even with the tendency of exacerbating the problem of oversupply in the affordable housing market segment.

Most importantly, one must question if such initiatives are backed by any supply-demand analysis. This is because a disproportion in terms of housing production and absorption is likely to aggravate the supply-demand conundrum; causing market cannibalisation to happen in the same housing market segment, where new launches tend to “eat up” the demand for the existing products, and eventually affect both the sales volume and market share of the existing housing stock.

To add salt to the wound, the take-up rate of price-controlled social housing is often lower than expected, owing to the dwelling conditions that limit its value appreciation; not to mention during the market slowdown period, consumer sentiment is low and the household income is stagnant (B40 in particular).

No shortage of supply

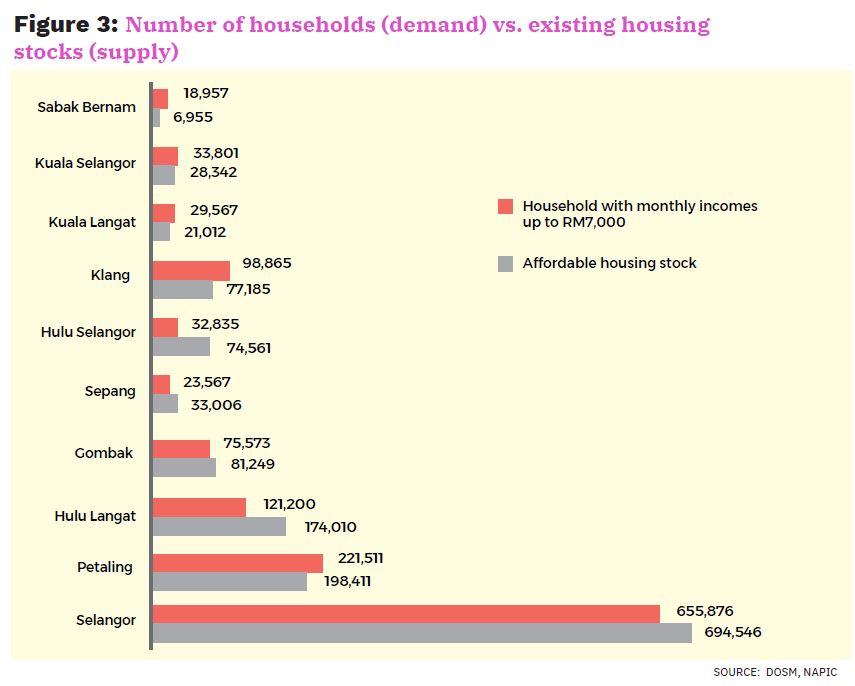

In fact, a study conducted by Real Estate & Housing Developers’ Association Selangor shows that there is no shortage of affordable houses in Selangor – being the most highly urbanised state in Malaysia. This is evidenced by comparing the existing housing stocks (representing the supply side) with the total number of households (representing the demand side) in the state (Figure 3).

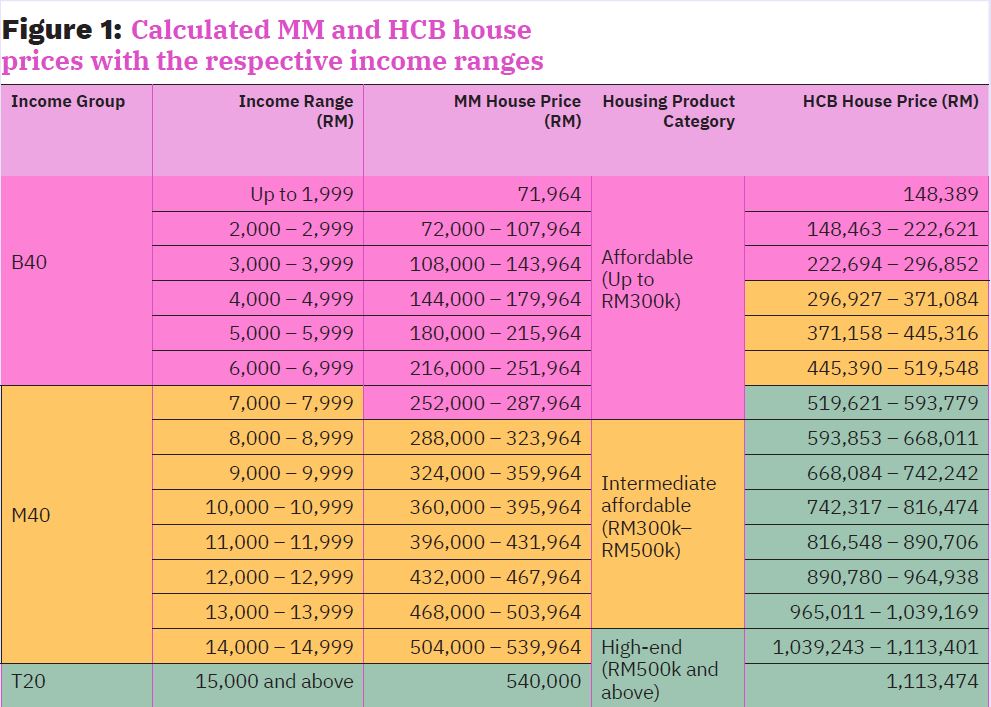

Based on the 2019 Household Income and Basic Amenities Survey Report, a B40 household in Selangor with a monthly income up to RM7,000 is financially eligible for houses priced up to RM252,000, calculated using the median multiple (MM) approach. An M40 household with a monthly income ranging between RM7,000 and RM15,000, on the other hand, is financially eligible for houses priced up to RM540,000.

To note, if the housing cost burden (HCB) approach is to be applied in this exercise – with the principle that monthly instalment should not exceed 30% of the total income, coupled with an indicative effective lending rate of 3.5% for a 90% mortgage loan over 30 years – the household affordability level is even higher.

A B40 household is deemed to be financially eligible for houses priced up to RM519,548, comprising both the “affordable” and “intermediate affordable” housing products; while an M40 household is to be served by those “high-end” products.

Clearly, we can safely assume that in Selangor, houses with capped selling price of RM300,000 are mainly catered for the B40 households with monthly incomes up to RM7,000. However, what we see is the current RSKU eligibility criteria has been extended to include those who earn up to RM10,000 for the sake of increasing the scheme’s take-up rate.

Meanwhile, based on the 24,275 raw transaction data in Selangor for the year of 2019 and 17,178 for the year of 2020; and to further compare the distribution curve of the raw data against those reported by the National Property Information Centre (NAPIC) that detailed the median, 25th percentile and 75th percentile; the number of properties within each product category at every price range is determined.

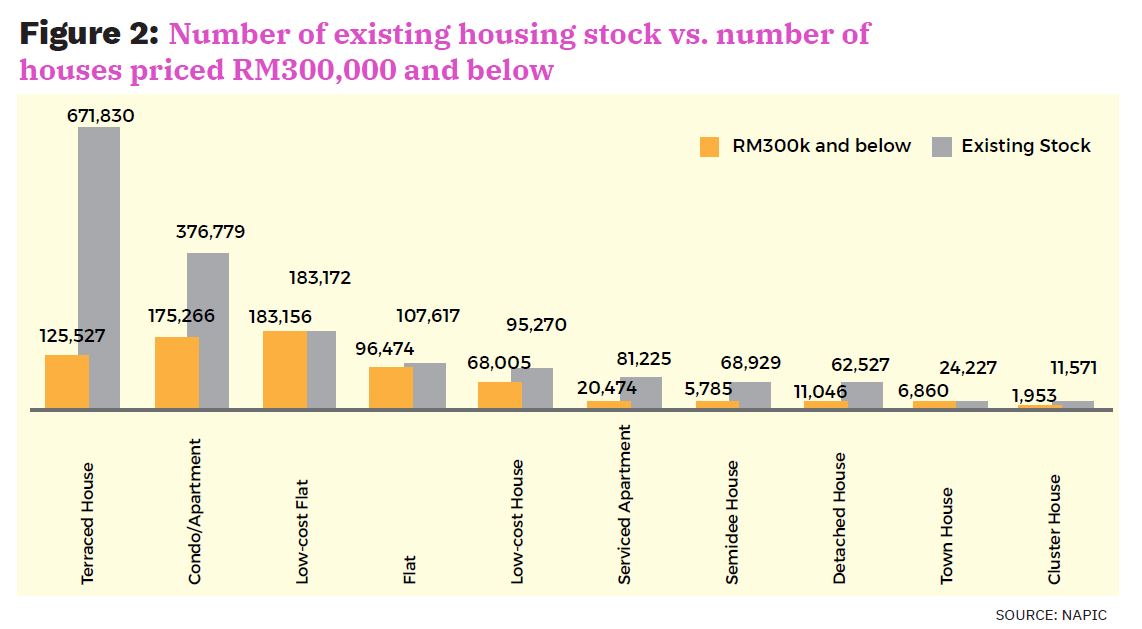

For example, the existing stock of houses (including serviced apartment) in Selangor amounts to 1,683,147 units as of 4Q2020, where 41% of them or 694,836 units are priced RM300k and below, which can be considered as “affordable houses” meeting the definition of Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) (Figure 2).

These “affordable houses” basically come from a wide range of product categories, ranging from low-cost flat (26.4%), condo/apartment (25.2%), terraced houses (18.1%), flat (13.9%), low-cost house (9.8%), serviced apartment (2.9%), detached house (1.6%), etc.

More houses than households

If we were to compare the number of households below the monthly income of RM7,000 against the stock of houses below the price of RM300,000; it is found that the state has, in fact, sufficient affordable houses to cater for the targeted households: 694,546 houses vs. 655,876 households (Figure 3).

Supply of affordable houses in most districts are found to exceed the demand (number of households), especially for those located within the Klang Valley region, and there are still affordable houses under construction and in the planning stage.

As long as the rate of supply outpaces the rate of demand, there should be no shortage of affordable houses across the state. Instead, what should be of more concern is the overbuilding of price-controlled social houses, with a high number of unsold units, low take-up rates and low marketability.

Of course, some may argue that the exercise should cover those who earn monthly incomes up to RM10,000, which is in line with the state’s price-controlled social housing scheme criteria. However, one should also realise that households with monthly income ranges of RM7,000–RM10,000 are financially eligible for houses with MM house prices of RM252,000–RM360,000, which have been covered by the current free-market housing products that fall under the category of “intermediate affordable houses”.

Notably, the demands of this category of households are different from the lower income group. They are likely looking for decent homes with value appreciation, more than just shelters that fulfil their basic needs. And obviously, from their perspective, buying a free-market product is more attractive than a price-controlled social housing, especially when the Home Ownership Campaign (HOC), with various incentives are being offered to lower the buyers’ entry level cost. Most importantly, the lifestyle, neighbourhood, and quality of living offered by free-market homes are perceived to be better, which are key to property investments.

The housing affordability crisis is often misunderstood as a lack of affordable houses in the market; and hence, the policy response will be diverted towards building “a discrete category of houses aimed at helping those deserving of aid”.

In reality, housing affordability does not necessarily mean the price of a house itself. Instead, the crisis refers to the fact that “one is spending more than 30% of his/her post-tax income on housing”. In this sense, the government should avoid falling into the pitfall of building more affordable houses when addressing the issue of housing affordability.

Though it is important to ensure there is enough supply of affordable houses in the market, the government must also realise the “side-effects” brought on by the blanket policy on mandatory building of affordable houses in the long-run; as it could potentially end up hurting every party in the housing industry, including those it intends to help.

Certainly, coping with the housing affordability crisis will require not only a renewed commitment to building more affordable houses; but also other structural economic adaptations like higher wages for service workers and better career pipelines. All these challenges and associated policy choices will need to be considered against the background of a “balanced housing industry ecosystem”, which is based upon the basic economic principle of supply-demand.

Dr Foo Chee Hung is MKH Bhd manager of product research and development and James Tan Kok Kiat is Suntrack Development Sdn Bhd chief executive officer. Foo and Tan are of the Planning Policies and Standard under the Real Estate Housing Developers’ Association

Never miss out

Sign up to get breaking news, unique insights, event invites and more from EdgeProp.

Latest publications

Malaysia's Most

Loved Property App

The only property app you need. More than 200,000 sale/rent listings and daily property news.