What is the plausible recovery trend for Malaysia post-Covid-19?

No one could have predicted the economic impacts of Covid-19 which have surpassed those of any other previous economic crises. While past crises recorded tended to impact only affected sectors or countries, Covid-19 is a communicable disease that spreads quickly across countries, and the associated economic costs are the consequences of needed containment measures for the pandemic — restricting travel, shuttering non-essential businesses, implementing universal social distancing policies, etc — which have halted a majority of business activities and caused a worldwide standstill.

When the virus outbreak just started and the movement control order (MCO) was first implemented in March 2020, many thought that the Malaysian economy would rebound in the second half of the year. But this hope faded along with the second and third waves of the outbreak.

Judging from the current development, where the mutations of the virus are still an ongoing threat, there will likely be no real recovery unless the virus is thoroughly eradicated.

So, here is the perception of the Malaysian economy in the next one or two years — it is moving towards the bottom with some industries grinding to a halt and registering negative growth, but it will not totally collapse due to the rapid government intervention to protect jobs and businesses.

However, no recession can last forever, and neither will the one we are facing now. A recession will always be followed by a recovery due to its cyclical nature. In general, there are four distinct recession and recovery shapes — V, U, W, and L — depicting the possible trends that could happen to the economy, from the best- to the worst-case scenario.

A V-shape is the best-case scenario, where sharp decline in the economy is immediately followed by a rapid recovery back to its previous peak, bolstered especially by economic measures and strong consumer spending.

• A U-shape could happen if the economy stagnates for a few quarters or up to two years, before experiencing a relatively healthy rise back to its previous peak.

• In a W-shape scenario, the economy falls into recession and recovers with a short period of growth; then falls back into recession before finally recovering, giving a “down up down up” pattern resembling the letter W.

• L-shape will be the worst-case scenario as it exhibits a sharp decline in the economy, followed by a slow recovery period that could take several years or even decades to recoup to previous levels.

The strength of the recovery

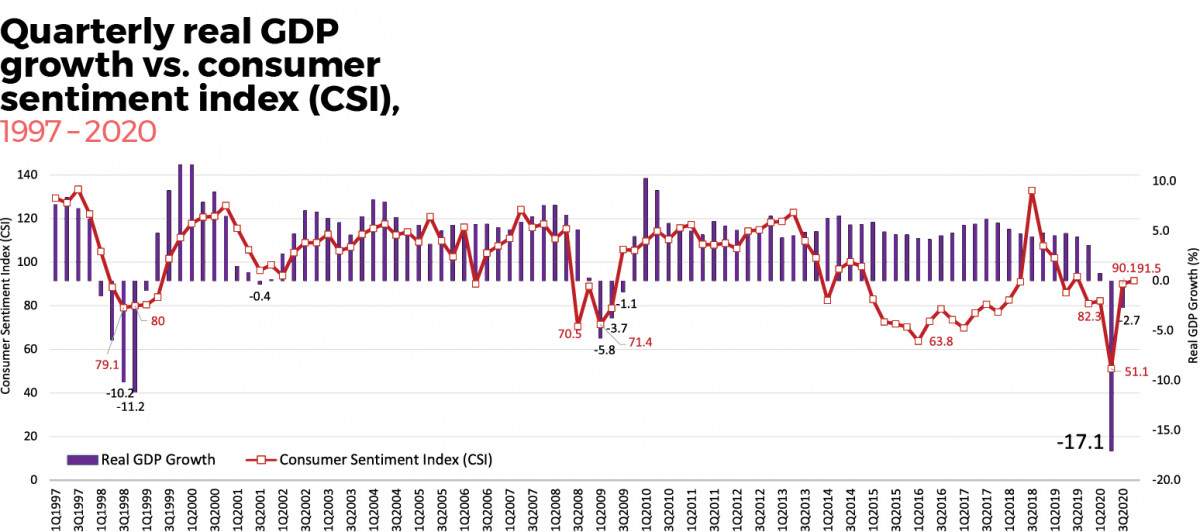

By studying the quarterly real gross domestic product (GDP) growth of the country throughout 1997–2020, one would find that Malaysia had experienced three periods of economic contractions prior to the Covid-19 recession: Asian Financial Crisis (1997–1999), Dot-com Bubble (2000–2002) and Global Financial Crisis (2007–2009).

Except for the one posed by Dot-com Bubble, the impacts of the other two crises affected the country significantly; where Malaysia’s GDP contracted 11.2% and 5.8% respectively during the Asian Financial Crisis and Global Financial Crisis; compared to a contraction of 0.4% incurred during the Dot-com Bubble (Figure 1).

One common feature of these past recessions is that they all showed a V-shape recovery, where the economy suffered a sharp decline with a clearly defined trough, followed by a strong recovery within five quarters.

The strength of the recovery is closely related to the severity of the preceding recession; where the more it declined, the higher level it reached after the recovery. Most importantly, the consumer sentiment index (CSI) follows the trajectory of GDP growth. As soon as the country’s economy shows signs of improvement, there is an increment in CSI.

Likewise, in the case of the Covid-19 recession, one can foresee the country’s economy is set to rebound, given the slower GDP contraction of 2.7% in the third quarter versus a 17.1% contraction in the second quarter of 2020.

This is also evidenced by the improved CSI from 51.1 in the second quarter to 90.1 and 91.5 in the subsequent third and fourth quarters, since the containment has been gradually relaxed, along with the reopening of commercial activities.

Coupled with other key economic tracking metrics, such as the increased volume and value of property transactions, the dropped unemployment rate and the increased bank loan applications, as well as the recent news on the availability of vaccine, the country’s economy will likely recover in a V-shape performance in 2021.

Nevertheless, the duration of the Covid-19 recession will only be obvious in hindsight. The recovery path is still fragile as the pace of recovery is no longer depending solely on how efficient Malaysia can limit both the health and economic damage from Covid-19, but also on how well other countries do in avoiding the prospect of an extended downturn.

If the rest of the world is still experiencing the virus outbreak, then our country’s borders will remain closed, and our economic recovery will still stall. In this sense, a U-shape recovery — indicating a longer recovery path — is likely to happen. Given that the consumer’s confidence is sensitive to adverse events, a W-shape could take place too, showing a tempting promise of recovery but dipping back into a sharp decline, if the vaccine does not show its expected effectiveness.

While an L-shape case is unlikely to happen, one should realise that those structural and fundamental weaknesses inherent in the country’s economic system — low income level of employees; lack of competitiveness; over-reliance on twin-oil commodities; outdated, inefficient and opaque government policies that suppress meritocracy; as well as slow adoption of new technologies that causes low productivity — still persist and are expected to aggravate due to Covid-19, thereby placing a drag on the overall economic recovery.

Though Malaysia’s economy has grown at a compound rate of 4.7% in the past 10 years, much of this growth has in fact been boosted by debt-fueled consumption binge. Investment — once the lifeblood of the country’s rapid economic development — has been taken over by both private consumption and government spending as the main growth drivers of the economy.

While consumption is still capable of being the engine of future growth, it is hardly being supported by the decreasing disposable incomes and the rising cost of living. One can observe that throughout 2015–2018, CSI was low even though the economic conditions were relatively good.

This is an obvious indication that the problem of income gap in the country has compounded; in addition to the introduction of the goods and services tax (GST) that led to a less optimistic outlook for most Malaysians.

Meanwhile, since the Asian Financial Crisis, banks have gravitated towards consumers and away from business loans. A significant portion of bank liquidity goes to mortgages and hire purchase. Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and startups with little financial track record and hard assets for security have limited funding operations. This has inevitably constricted the entrepreneurship, innovation, as well as higher productivity growth of the country’s economy.

More catalysts needed for private sector

One should realise that, in a recovery market, the movement will only go up if the private sector can access more and cheaper credit. This is because such an initiative will incentivise the private sector to invest, to make money, and to create jobs that lead to higher incomes for both Malaysian workers and the country.

Given that SMEs are the backbone of the country’s economy that account for the majority of employments and job creations, the collapse of SMEs will surely push up the unemployment rate while lowering the overall consumption power.

The shrinking consumption power will then intensify the market recession and further damage the already sluggish economy. As such, from a macroeconomic perspective, the government should place more emphasis on helping industries and businesses to survive, to grow and to transform.

It is time for the government to undertake reform, so as to rebuild the country’s strengths and to prepare for the future. Reforms should not only address the immediate economic vulnerabilities, which include enhancing the fiscal position and strengthening household resilience; but should also focus on rejuvenating private-sector-led investments.

This will not only ensure a sustainable growth, create jobs, raise the overall productivity and per capita income, which, in turn, will underpin domestic consumption growth and lift the living standards of the people; but also will help in strengthening the country’s competitiveness once the country reopens its borders after the pandemic.

Dr Foo Chee Hung is MKH Bhd manager of product research & development

This story first appeared in the EdgeProp.my e-Pub on Dec 25, 2020. You can access back issues here.

Get the latest news @ www.EdgeProp.my

Subscribe to our Telegram channel for the latest stories and updates

Never miss out

Sign up to get breaking news, unique insights, event invites and more from EdgeProp.

Latest publications

Malaysia's Most

Loved Property App

The only property app you need. More than 200,000 sale/rent listings and daily property news.