Lessons from Japan's public housing

After World War II, there was a shortage of homes in Japan as many had been destroyed by aerial bombings.

“We had to build more homes for the people, especially those who needed affordable homes,” Japan’s Parliamentary Vice-Minister for Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT) Masamune Wada said in a recent meet-up with Malaysia Housing and Local Government (KPKT) Minister Zuraida Kamaruddin.

Read also

Housing minister and developers find inspiration in the Far East

EdgeProp Study Tour: An opportunity to gain ideas and network

Why we need air quality regulations

Creating values worth paying for

Design for productive workplaces

How do we prevent bad indoor air quality?

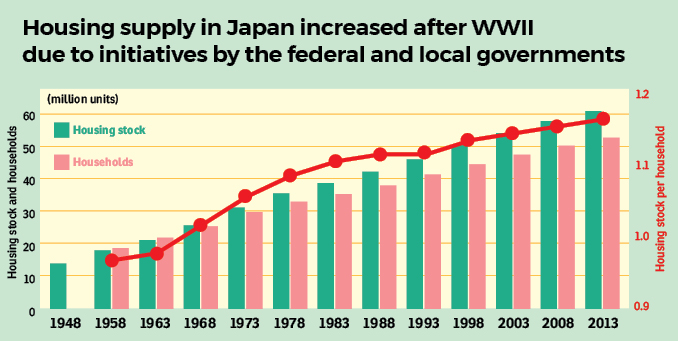

According to MLIT, there was a shortage of about 4.2 million homes in 1945. However, with the public housing initiatives by the government, the situation began to improve as housing supply increased gradually.

Wada’s meeting with Zuraida was facilitated in conjunction with the EdgeProp Malaysia Study Tour on Excellent Building Sustainability, Management and Wellness 2019 in Japan from Oct 3 to 5.

The study tour was organised by EdgeProp Malaysia and supported by Panasonic. Among the 34 delegates were leaders of top property development companies in Malaysia and judges of EdgeProp Malaysia’s Best Managed Property Awards.

During their meeting, Zuraida and Wada exchanged notes on their respective countries’ public housing system and their efforts in providing affordable homes for their people.

In a separate briefing to Zuraida, MLIT’s deputy director of international affairs office under the general affairs division of housing bureau Takeru

Kosaka said one of the Japanese government’s initiatives to raise housing supply after WWII was to build rental homes for low-income earners.

“In 1951, local governments have [started to] provide public [rental] housing with low rents for the low-income group. There were also initiatives such as providing low-interest long-term housing loans to homebuyers and building more houses in major cities where the population and housing demand are high,” he shared.

As a result, the total housing supply exceeded the total number of households in the country by 1968.

Subsequently, in 1973, the number of housing stock exceeded the total number of households in every prefecture which meant there were sufficient housing units to cater to the demand in each prefecture.

As of 2013, there were some 60.63 million units in housing stock while the total number of households stood at 52.5 million — which meant that a sufficient number of housing supply has already been secured.

Food for thought

Under Japan’s public rental housing schemes, the construction cost is borne jointly by the federal government and local authority, with the latter taking care of the land purchase cost to ensure the affordability level of these homes for low-income earners.

Managed by the local authorities, these rental homes are open to the B40 group, which has been defined based on the average income level in each prefecture. The rent rates of these homes are set based on the tenants’ monthly incomes.

The local authority keeps track of the income levels of the tenants and once their income levels exceed the B40 level, they are no longer eligible to rent these homes and will have to give way to those eligible.

What caught Zuraida’s attention was how the low-income group in Japan is divided into two categories, namely the lowest B17 category and the B17 to B40 category.

“This gives me an idea to break the B40 grouping down to the B20 or B10 so that it would be more effective and targeted in solving the homeownership difficulties faced by the lower income group.

“For example, the rent-to-own schemes that we have in Malaysia are trying to serve the B40 group which consists of various earners at different income levels,” she says.

She adds that providing affordable homes to the rakyat is at the heart of the Pakatan Harapan government’s policies and it has been working with several parties such as financial institutions to offer low-interest housing loans to the low-income group.

Enhancing the liveability of public housing

The Housing Minister also took note that Japan’s Building Standard Law has been regulating indoor air ventilation for about 16 years.

“Maybe, that will be something we can modify to our standards in order to ensure that the B40 or the masses back home can enjoy the basic right to quality air,” she told EdgeProp.my after the briefing.

The Building Standard Law was amended in July 2003 to include provisions related to indoor air quality to tackle the Sick House Syndrome.

The Sick House Syndrome refers to a medical condition where building occupants suffer from symptoms such as eye, ear, nose and throat irritation due to toxic chemicals such as formaldehyde, toluene and chlorpyrifos emissions from building materials and furniture.

The law states that all habitable rooms must have windows and other openings for ventilation, otherwise ventilation equipment must be installed. Apart from that, the law also prohibits the use of building materials containing chlorpyrifos in buildings with habitable rooms.

Enhancing the quality of life of those who are living in Malaysia’s public housing schemes is one of the objectives of the National Community Policy (DKN) formulated by the housing ministry.

DKN is a feature of the National Housing Policy or Dasar Perumahan Negara 2018-2025 that aims to empower the lives and improve the living environment of the B40 group.

“It is never too late for Malaysia to adopt some of the measures that other countries have been implementing for a long time. With some improvising and fine tuning, we will be able to solve the issues plaguing the local housing market,” said Zuraida.

This story first appeared in the EdgeProp.my pullout on Oct 18, 2019. You can access back issues here.

Follow Us

Follow our channels to receive property news updates 24/7 round the clock.

Telegram

Latest publications

Malaysia's Most

Loved Property App

The only property app you need. More than 200,000 sale/rent listings and daily property news.